A major challenge for businesses, teams, and architects is identifying and managing significant changes to an architecture. By significant, we refer to the cost or effort required to implement the change and the value it delivers to the business. Architecture initiatives frequently fail to meet timelines and budgets when the significance of a given change is underestimated. What may initially appear to be a simple architectural adjustment can ultimately have major consequences for the business, resulting in increased effort.

A request to change the architecture is often presented as a proposal outlining the changes to be carried out. This can take the form of a verbal discussion, a presentation at a meeting, a story in a backlog, or more formal requests such as an Architecture Change Request (ACR) or an Architecture Decision Proposal (ADP). These change requests may include several alternative proposals that describe different ways to achieve the same business value, requiring a decision on which option is most appropriate.

The architect is tasked with assessing the significance of each proposal to ensure it is feasible, and based on the assessment make decisions or provide recommendations to stakeholders regarding which proposals to pursue. Carrying out an assessment on change proposals before execution reduces risk to the business, provides context, highlights consequences and prepares a proposal for execution. Through an assessment the architect can gain insights to the significance of a proposal which gives an indication of how much up-front planning is required, and actions that may be needed before a decision can be made. Proposals of a simple nature may only require a short assessment and can be quickly decided upon. However, more complex proposals may require several meetings, investigations or a study before a decision can be taken.

There are several important aspects to assessing a proposal. The PREVAIL approach provides a mindset which supports architects when working with assessments and can be used both with informal and formal proposals.

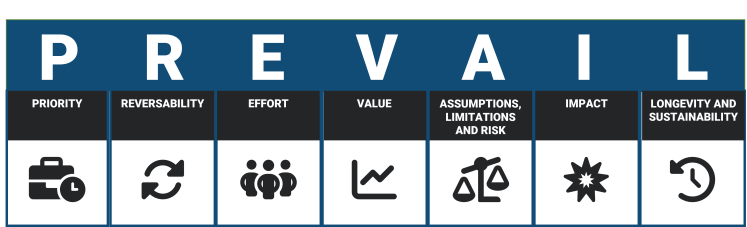

PREVAIL

The PREVAIL approach highlights a number of key factors that can be used to assess a proposal and establish a basis for decision-making.

- Priority

How quickly does the business need to deliver the proposal? - Reversibility

Can the proposal be reversed? - Effort To Execute

How much effort is required to execute and deliver the proposal? - Value

What value does the proposal deliver to the business? - Assumptions, Limitations and Risk

Are their uncertainties and constraints that are associated with the proposal? - Impact

What is the effect of the proposal on the scope and operation of the business? - Longevity and Sustainability

Is the proposal maintainable and sustainable over time?

Priority

Priority refers to how quickly the business needs to deliver the proposal. This is associated with specific deadlines and calendar time for delivery. It may be driven by several factors, for example:

- Business Opportunity

The business may have an opportunity in a market or with a customer that exists within a given timeframe, offering an advantage over competitors. - Regulation and Law

Changes in regulation and law require compliance and often come with a deadline. Failure to comply can have serious consequences for the business. - Contract Obligations

Contractual obligations to customers or suppliers may require the business to deliver products or services within a specific timeframe. - Audit Deviations

Findings from audits may uncover deviations that represent a major business risk—such as security vulnerabilities. Modifications to resolve such deviations often carry high priority. - Maintenance and Deprecation

End-of-life for technology products, or operating unsupported product versions, represents a significant business risk. Vendors often publish a roadmap of supported versions with specific dates and provide advance warnings of end-of-life. This can drive specific deadlines for upgrades or migrations.

Different stakeholders within the business have different priorities, so it is worthwhile to note which stakeholders are driving the priority of the proposal. If there is no clear priority, it raises the question of whether there is any motivation to execute the proposal at all.

High-priority proposals may require intensive effort to meet deadlines, manage stakeholders, and balance scope and resources. This increases the significance of the proposal, and such proposals often need to detail timelines, dependencies, and required resources before a decision can be made.

Reversibility

Reversibility is the degree to which an architectural decision or change can be rolled back with minimal effect on the business. Reversibility is important when assessing the risk of a proposal, where high reversibility represents low risk, while low reversibility represents high risk.

For example, a patched logging component may have a high level of reversibility, as it may be quickly reversed by re-deploying a backup of the previous version of the component. However, modifications to a database managing financial transactions in real time may have a low level of reversibility if transactions are difficult to reverse once the database is live.

Proposals with high reversibility require less effort to reverse, while proposals with low reversibility may require significant effort to reverse and can severely disrupt business. The effort required to reverse a change may be applied to undoing the changes that affect technologies, processes, and people. In extreme cases, reversal may not be possible, this means the business will be tasked with firefighting to resolve issues while the system is in operation.

Before a decision can be made on a proposal with low reversibility, consideration often has to be given to consequences, planning preventative actions, and provisioning of contingency plans.

Effort To Execute

In order to execute and deliver a proposal, effort is required from the business. This may be effort from many different stakeholders, for example, developers, subject matter experts, product owners, or operations personnel. This effort can be measured in the hours or expenditure from resources that are needed to perform the work. These resources may be internal or external to the business.

The following are examples of areas that can drive effort in executing a proposal:

- Expert Skills

Finding resources with expert skills can be challenging. Effort may be expended in finding the right resources internally or externally. If the skills are not available internally, extra costs may be incurred to obtain external resources such as consultants. If the required skills are specific to the business, they may not be available externally, and internal training may be necessary. - Availability

Internal competition between assignments can limit the availability of critical resources. When resources are shared across assignments, dependencies are created that may require effort to manage internal politics. This sharing also demands more planning and increases the risk of delays if resources are not available as anticipated. - Third-party Actors

If the proposal relies on third parties, substantial effort may be required in planning and collaboration during execution, especially where significant dependencies exist between activities shared by the parties. - Geographical Location

If the teams executing the proposal are placed in different geographical locations, more effort in planning may be required. Working across several time zones with different cultures may require more effort in collaboration.

A proposal that requires considerable effort to execute is likely to require a time plan, resourcing plan, and estimate before a decision can be made.

Value

Value provides the justification of the proposal and is central to assessing the its significance. Since stakeholders have different interests, what one considers valuable may hold little relevance for another. As a result, determining value can be subject to political influence within the business.

The following are some examples of types of value:

- Customer Satisfaction

Satisfied customers ensure that the business can retain and expand its customer base. - Increased Profitability

The provisioning of services or products provides opportunities to increase profitability. - Improved Maintainability Improving the maintainability of systems and services facilitates business agility and reduces costs.

- Operational Efficiency

Automating operational processes can reduce operating costs. Improvements to factors such as scalability, performance, or manageability can act as a facilitator for expanding the business’s market share. - Risk Mitigation

Improvements in areas such as security, reliability, or governance can reduce threats to business operations.

The value of a proposal is often weighed against the effort required to deliver it. Proposals that offer minimal value relative to their effort are unlikely to be worthwhile. Those that deliver high value to the business typically carry greater significance, as they provide substantial benefits to stakeholders.

Assumptions, Limitations and Risk

When detailing a proposal, the requestor of the change may not be in possession of all the required information and therefore has to make assumptions. A proposal with a high degree of assumptions can represent significant uncertainty. An assumption that turns out to be incorrect or over optimistic can change principles, designs, expectations and require more effort than expected.

Limitations are constraints that are placed on the proposal, these may be internal or external. When executing the proposal these can limit the room for maneuver since they reduce the options the architect has when tackling issues. Limitations which impose a narrow path to success can result in a brut force approach since there is only one way forward. A high degree of limitation associated with a proposal can raise serious concerns since working with these constraints may demand considerable time, effort, and resources, potentially impacting the feasibility and success of the proposal.

Both assumptions and limitations can be treated as risks. In addition to these, a proposal may be associated with various other types of risk, for example, financial, legal, technological, or business-related.

Risk is key in the decision-making process and needs to be weighed in terms of probability and consequence. Proposals with a high risk rating can be regarded as having considerable significance since substantial effort may be required for mitigation and management of consequences if a risk becomes reality. Proposals with a sizable risk factor often require an analysis of consequences and a plan for risk mitigation before a decision to execute the proposal is made.

Impact

Impact refers to the degree of change a proposal will have on the surrounding business. This can be thought of as the ripple effect, where a change in one area of the business can trigger a series of consequences, both intended and unintended, across other parts of the organization. Sometimes, what seems like a trivial or isolated change can lead to widespread effects on people, processes, systems, and outcomes.

Assessing impact is key to understanding how extensively a proposal will influence the architecture, business operations, and strategic goals. Underestimating the impact of a change can lead to resistance, unanticipated costs, or even failure of the proposal if consequences are not properly managed or communicated.

The following are examples of areas to consider when assessing the impact of a proposal:

- Systems

A proposal may drive changes to several systems may be required which increases complexity and effort. These systems may be internal to the business or external systems. - Products and Services

Existing products and services may have to adapt to the proposed changes. This can impact customers and third-parties such as suppliers or partners. These stakeholders need to be managed to ensure a smooth delivery of the proposal. - Business Scope

Impact on business scope refers to the extent to which different levels of the business or organization are affected. For example, a proposal may have a limited impact, affecting only a small number of internal departments, or it may have a broader impact reaching across national or even global parts of the organization. - Business Processes

Changes in an architecture can affect both the people and processes within the business. Ways of working may need to be adjusted, and new roles or responsibilities may need to be introduced to fully realize the benefits of the proposal.

A high level of impact can incur substantial effort on a proposal during execution. Before making a decision on a proposal with a major impact, it is likely that a strategy or plan will be needed to show how impact can be managed.

Longevity and Sustainability

Expectations around the longevity and sustainability of an architectural change can influence how a proposal is assessed. Changes may be intended to remain a core part of the architecture throughout its lifespan, or they may introduce a short-term fix meant to stay in place only until the architecture is redesigned or decommissioned. A common problem is that changes which were intended as a short-term fix sometimes become woven into the long-term architecture. This can lead to architectural degradation, since short-term fixes tend not to be sustainable.

Assessing the longevity and sustainability of a proposal is essential to ensure that value is not only delivered after the execution of the proposal, but can continue to be delivered throughout the expected lifetime of the architecture.

The following are examples of areas to consider when assessing the longevity and sustainability of a proposal:

- Expected Life-Time

An architecture may be expected to remain maintainable over many years. This expectation should be considered during the assessment to ensure that both the design and implementation support long-term maintainability and help avoid excessive costs in the future. - Technology Obsolescence

A proposal may rely on specific technologies for execution and implementation. It is important to consider the life-time and supportability of these technologies so they are aligned with the expected life-time of the architecture. - Vendor Lock-In

Technologies from third-parties may result in dependencies on specific vendors. The use of vendor specific standards instead of open standards can make technologies difficult to replace and the use of niche technologies may reduce the ability to secure support. - Support

Technologies used in the architecture should have sufficient support to span the expected lifetime of the change. It is important to assess the stability of the technology providers involved in the proposal. If a provider is not well established, there may be a risk of bankruptcy or acquisition by another company, which could result in changes to support terms, conditions, or availability. - Adaptability

Consideration needs to be given to the effect of the proposal on the adaptability of the architecture. Being able to easily adapt the architecture facilitates the avoidance of degradation and helps to keep pace with the surrounding technology landscape as it changes. - Resource Efficiency

Resource efficiency refers to the operational use of resources such as data centers, servers, networks, and storage. A proposal may be assessed based on sustainability factors, including energy efficiency and the application of Green IT principles.

Proposals expected to be maintained over a long-term lifespan require careful consideration of longevity and sustainability. Assessments of technologies, vendors, and support may be necessary before a decision to execute the proposal can be made.

Summary

Architectural change can have significant implications for business which can result in unexpected costs and severe consequences. The PREVAIL approach offers a structured approach to assessing proposals, both formally and informally. The approach uses seven key factors to help architects and stakeholders understand the significance of a proposal, plan appropriately, manage risk, and align with business objectives. Using PREVAIL provides a repeatable process for making informed decisions, increases the likelihood of success, and promotes long-term architectural sustainability.

The Architecture Mindset Articles by Stephen Dougall are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.